Mastering ESPPs (Employee Stock Purchase Plans)

A guide for advisors helping clients navigate equity, avoid tax surprises, and optimize outcomes

Qualifying ESPPs are a common employee benefit at public companies and one of the easiest places for even experienced clients to misunderstand how it impacts their financial situation.

On paper, it sounds simple: “I contribute through payroll, buy shares at a discount, and hopefully sell for a gain.” In real life, ESPPs create a three-way collision between cash flow planning, tax rules, and brokerage reporting. That collision is where clients get surprised… and where great advisors deliver value.

This guide focuses on how to help clients (1) understand ESPP participation mechanics, (2) know what gets taxed and when, and (3) report the sale correctly.

Qualifying ESPPs 101: The six terms that drive everything

What are qualifying ESPPs? Qualifying ESPPs are employer stock purchase plans that allow employees to buy shares at a discount through payroll deductions, with taxation deferred until the shares are sold if certain holding requirements are met.

Most ESPP confusion starts with vocabulary. A qualified ESPP is built around a few recurring plan concepts: offering periods, purchase periods, an enrollment/grant date, a purchase date, the discount/lookback, and a purchase price.

Here’s the advisor-friendly translation:

- Offering period: The “container” timeline during which purchases can occur (often 12 or 24 months).

- Enrollment date (grant date): The start of participation for that offering period.

- Purchase period: Sub-periods within the offering period (commonly 6 months) where payroll deductions accumulate and then buy shares on a set purchase date.

- Purchase date: The day shares are purchased (usually the end of the purchase period).

- Discount + lookback: Qualified plans commonly offer up to a 15% discount, and some include a lookback that sets the purchase price using the lower of the enrollment-date price or the purchase-date price (then applies the discount).

- Purchase Price: The price paid for shares, the number of shares purchased is then determined by the amount of contributions during the Purchase Period.

Setting proper expectations for cash flow and after-tax outcomes depends on an advisor’s ability to contextualize these aspects of ESPPs so clients can make informed decisions around participating and liquidating their ESPP shares.

The Cash Flow Conundrum: payroll deductions sound smaller than they are

Why do ESPP payroll deductions feel smaller than they actually are? A practical planning point that gets missed: ESPP contributions are typically elected as a % of compensation, but the deductions come out of after-tax pay. That can create a bigger-than-expected hit to take-home pay - especially for clients also maxing retirement plans, HSA, mega backdoor, etc.

When helping a client decide if they want to participate in their employer’s ESPP, it’s important to first have a clear understanding of their cash flows.

Advisor move: treat ESPP participation like a recurring goal-based savings decision. Confirm:

- the client’s contribution rate and impact on a per pay period basis,

- whether the household’s monthly cash buffer or excess cash holdings can absorb it,

- when they have the ability to sell purchased shares irrespective of tax impact

This is where you reduce stress and prevent cash flow pinches when the inevitable unexpected spending crops up.

The Tax Map: 3 dates, 2 holding periods, 2 tax buckets

How are ESPPs taxed across purchase, holding, and sale? ESPP taxation hinges on three key dates, two holding period tests, and a split between ordinary income and capital gains at sale.

Step 1: Confirm it’s a “qualified” ESPP (IRC Section 423) and the specific plan structure

Qualified ESPPs have special tax treatment governed by Internal Revenue Code Section 423. The IRS limits purchases under the plan to $25,000 worth of stock value.

When an Offering Period spans multiple calendar years, if a participant does not purchase a full $25,000 worth of stock in the first year of the offering, the unused portion of the limitation can be carried forward to the next year and increases the amount of stock the participant can purchase in that year.

Calculation of the maximum is based on the undiscounted Purchase Price at the start of the Offering Period.

Step 2: Know when tax happens

For qualified ESPPs, no income is recognized at purchase; tax is triggered when the shares are sold.

Step 3: Apply the holding periods

A qualifying disposition generally requires holding the shares at least 24 months from the enrollment/grant date and 12 months from the purchase date.

If either requirement isn’t met, it’s a disqualifying disposition.

Step 4: Split the sale proceeds into two tax buckets

Every ESPP sale has two potential components:

- Ordinary income (compensation) is related to the discount received on the purchase price

- Capital gain/loss is related to difference between the sale price and the discounted purchase price

This is where double taxation erroneously happens due to misreporting on the tax return. The compensation component needs to be reflected in the cost basis but is usually not reported on the 1099.

What is the difference between a Qualifying and Disqualifying Disposition?

Example: Company allows contributions up to a limit of $25,000 per year. ESPP offers a 15% discount with a lookback. This means the maximum annual contribution is $21,250.

- Enrollment date FMV: $100

- Purchase date FMV: $110

- Purchase Price: $85 ($100 minus the 15% discount)

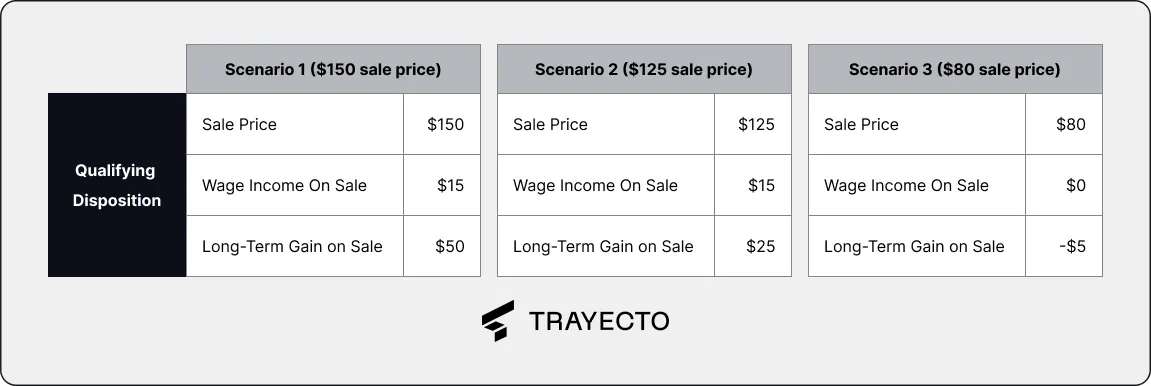

Qualifying Disposition (optimal tax treatment)

In a qualifying disposition, the ordinary income is generally tied to the discount, but it’s limited. The amount of the discount you received (to be taxed as ordinary income) calculated as the lesser of:

- The FMV of the company stock on the Enrollment Date x the ESPP discount rate

- The sale price - the FMV of stock on the Enrollment Date

EX:

- If the client sells at $150, wage income is $15/share (the $100 enrollment FMV minus $85 purchase price), and the remaining appreciation of $50 is long-term capital gain.

- If the client sells at $125, wage income is still $15/share, and long-term gain is the remaining appreciation of $25.

- If the client sells at $80, below the purchase price, there would be no wage income. The $5 per share difference would be a long-term capital loss.

Advisor framing: “Qualifying dispositions can convert more of the outcome into long-term capital gains, but the plan rules only ‘rewards’ you if you can tolerate the holding period and concentration risk.”

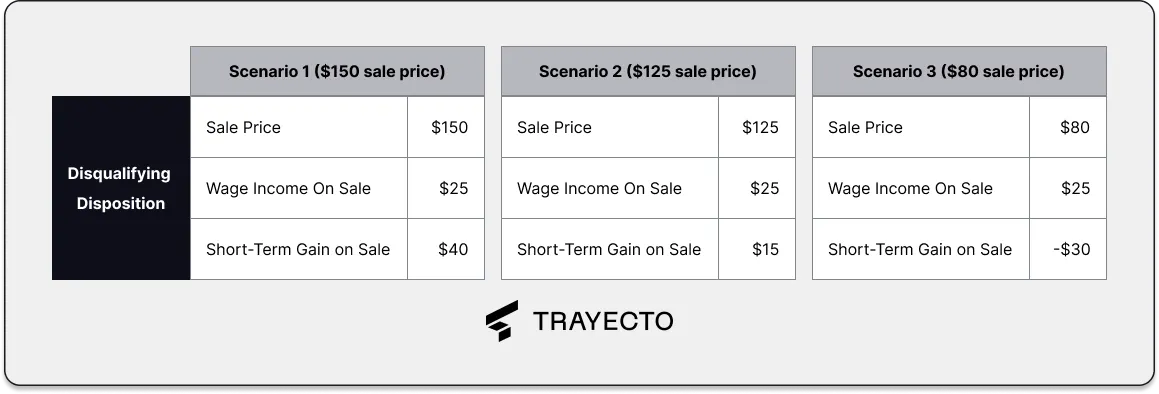

Disqualifying Disposition (common in real life)

For disqualifying dispositions, the ordinary income is typically larger because it uses the purchase-date FMV relative to the purchase price. This is part of the tax benefit that the transaction does not qualify for due to the holding period rules not being met. Following the same example as above:

- If the client sells at $150, wage income is $25/share (purchase-date FMV $110 minus purchase price $85), and the remaining appreciation of $40 is short-term capital gain.

- If the client sells at $125, wage income is still $25/share, and short-term gain is the remaining appreciation of $15 is short-term capital gain.

- If the client sells at $80, they still incur wage income of $25/share, along with a $30 short-term capital loss per share to reflect the net $5 loss on the transaction.

Advisor framing: “Disqualifying isn’t ‘bad’, it’s just different. Many clients sell immediately to reduce concentration risk and recoup their contributed cash as quickly as possible. I will help make sure you understand the cash flow and tax implications while coordinating with your tax pro to ensure sales are properly reported.”

Form 3922: the document that quietly prevents overpaying

What is Form 3922 and why does it matter for ESPP reporting?

- Form 3922 is issued when an employee purchases shares through an ESPP and helps track cost basis adjustments for accurate reporting when shares are sold.

- It includes critical inputs like grant/enrollment date, purchase date, purchase price, FMV on both dates, and the number of shares purchased on each purchase date in that year.

The mistake: clients (and even some preparers) ignore Form 3922 because it’s “informational.” In practice, ignoring it is how you get:

- overstated capital gains,

- double taxation (wages + capital gains on the same value),

- and avoidable amended returns.

The Reporting Trap: 1099-B basis is often missing or wrong

Why is the cost basis often wrong for ESPP sales on the 1099-B? And what can you do about it?

Stock plan custodians will report ESPP sales on the 1099-B as “non-covered transactions”, meaning that the cost basis is not reported to the IRS. The cost basis for those sales will also usually show as $0 on the 1099-B.

However, the wage income component of any ESPP sales will show up on a W-2 from the employer in the year of sale.

To help make sure your clients don’t overpay taxes on their ESPP sales:

- Match the 1099-B from the year of sale to the Form 3922 from the year of purchase to determine the accurate cost basis.

- Request and review the 1099 Supplemental from the custodian in the year of sale, which should report the adjusted cost basis for each ESPP sale.

- The tax preparer should reconcile the cost basis adjustment on the sale using the 1099 Supplemental and/or the 3922.

The capital gains or losses incurred from an ESPP sale that are reported on the return should be correct when reconciled appropriately.

Advisor Edge: a simple ESPP playbook you can repeat

1) Build the “ESPP lot ledger”

For each purchase period, record:

- enrollment date + FMV

- purchase date + FMV

- purchase price

- shares purchased

- Sale date and price

You can do this manually in a spreadsheet or by streamlining it in Trayecto’s software.

2) Ask one question that informs that financial plan

“Are you selling immediately, or are you intentionally trying to qualify?”

Then explain the tradeoff in plain English: potential tax benefit vs. concentration risk + timeline.

3) Pre-file reconciliation (the “no surprises” standard)

Before filing, reconcile:

- Form 3922 (inputs)

- W-2 (any ESPP wages)

- 1099-B + 1099 supplemental (reported proceeds/basis)

If you only adopt one new process for clients with equity comp, make it this.

4) Tie ESPP decisions to goals, not tax treatment

Clients don’t win because they memorized the holding period rules. They win because you connected ESPP proceeds to something concrete: emergency reserves, tax payments, a home down payment, education funding, or reducing single-stock risk.

Final Thought

Just because ESPPs are common and “simple” doesn’t mean you can’t add value or clients don’t deserve in-depth analysis. Helping clients avoid tax shocks, address reporting issues, and fund their goals transforms equity into empowerment. For advisors who want to stand out in the tech niche, mastering ESPPs is the table stakes.

If you don’t have access to software that helps you streamline equity comp planning, request a demo of Trayecto.

Related guides